As an AI company that works with images, we pay attention to what happens when a camera stops being “just a camera” and becomes an identification tool.

One clarification up front: tools that enhance faces are not automatically “facial recognition.” LetsEnhance, for example, is an image quality product that upscales, deblurs, denoises, and restores photos, including portraits. It doesn't identify people. That distinction matters because the privacy risk usually comes from identity linking (verification, identification, tracking), not from making an image sharper.

Facial recognition isn't new. What is new is how quietly it has become default in phones, airports, workplaces, and public spaces, often without users making an informed choice.

There is a saying: “One person’s freedom ends where another’s begins.” The same applies to privacy. A face isn't only personal data. In the wrong context, it becomes an identifier that follows you across systems. The article shows how facial recognition works, where it is used today, why it fails in ways that matter, and what regulation and engineering controls actually reduce harm.

What facial recognition is (and what it isn't)

People call a lot of things “facial recognition.” They aren't the same problem.

- Face detection: finding a face in an image (bounding box).

- Face analysis: extracting attributes like age estimate, emotion inference, or gaze direction.

- Face verification (1:1): “Is this person the same as the ID on file?” Used for device unlock, border checks, account recovery.

- Face identification (1:N): “Who is this person among many?” Used for watchlists and investigative search.

- Face tracking: following a face across frames or cameras, sometimes without knowing who it is.

Privacy risk climbs fast as you move from detection to identification, and then to tracking.

Do you remember the “aging app” moment?

A few years ago, FaceApp made people upload portraits to see themselves “older.” The backlash wasn't really about wrinkles. It was about consent, retention, and where face data goes once it leaves your phone.

The pattern didn't disappear. Generative AI made face edits easier, more realistic, and easier to automate. The privacy lesson stayed the same: face images are high-value inputs because they can be used for identity linking, not just editing.

But if we delve into the situation, we are under surveillance all the time. Look at your phone, your nearest ally is watching you all the time. You bypass the smartphone's facial recognition security everyday. Afterwards, you enter to check your bank account balance using your face. Then you entertain yourself with any funny face app or maybe check the house control app, or finally go into a restaurant and pay there with your face again.

How does it work?

Just as with neural networks, the facial recognition system works the same as a human one. Your eyes capture the face scene. Then it is sent to your mind to be processed. Afterwards, your memory recalls the identity by its features.

But imagine, if you could have thousands of eyes?

What if all the information from them you can store as memories from other people? And all of it can be processed simultaneously.

Facial recognition neural networks make just the same process as your brain's visual cortex does. It’s scanning faces by measuring the distance between eyes, nose, mouth and checking other features. These algorithms look for a correlation in raw pixel data.

A useful parallel: image enhancement models work on a different problem than recognition models. Recognition tries to map a face to an identity embedding. Enhancement tries to reconstruct plausible high-frequency detail when the original signal is missing (blur, compression, low resolution). That’s why an upscaler can make a face look “more real” without knowing who it is.

Networks are fed with the original photo, other photos of this person and with a photo of another person. And the system should tell the difference between absolute similarity.

But frankly speaking, we built this ‘Mind of facial recognition system’ by ourselves. We are posting millions of digital photos into Facebook, Google, Instagram, Twitter every day. What’s more, we are tagging ourselves and friends of us.

What benefits for “mere mortals”?

Not all use cases are dystopian. The practical appeal is time and friction reduction.

Device unlock and account access: Users prefer fast authentication over passwords. That is why “face unlock” spread so quickly.

Travel and border processing: Airports are controlled environments, which is why face verification is operationally attractive. Some programs present this as opt-in and offer alternatives, but implementation varies by airport and flow.

Payments and banking: Biometrics reduce certain fraud types, but they also create new failure modes. “Face as a payment credential” is only as safe as the fallback process, liveness checks, and retention rules.

E-commerce and try-on: Virtual try-on and “visual mirrors” are now common. This can be done without identifying a person, but in practice many systems drift from “try-on” into “profiling.” The line is a product choice.

Important distinction: face detection and face effects aren't the same as face identification. The privacy risk spikes when a system is used to uniquely identify people or track them across contexts.

What about the government level?

In the United States, the regulatory story is still fragmented. There is no single, comprehensive federal law that sets a uniform standard for when government can deploy facial recognition. That vacuum is why the early pushback happened city by city.

Some cities have banned government use outright. San Francisco passed a surveillance oversight ordinance in 2019 that bans city departments from using facial recognition technology. Somerville, Massachusetts became the first city on the US East Coast to ban government use of face surveillance in 2019. Oakland followed with a ban covering city departments, including police.

It's important to be precise about what these laws do. Most municipal bans target government use and sit alongside broader surveillance oversight rules, such as public reporting and approval requirements for other surveillance tools. They generally don't ban private use by businesses, and they don't stop data from flowing in via third parties.

Europe moved from “considering” to “legislating.” In early 2020, a leaked draft discussed a time-limited moratorium on facial recognition in public spaces, framed as a pause to develop risk assessment and safeguards. That moratorium didn't become the final approach. Instead, the EU adopted a risk-based regime in the EU AI Act, which includes strict limits on remote biometric identification, especially “real-time” use in publicly accessible spaces, with narrow exceptions for serious cases and additional oversight requirements.

Sweden was an early signal of how regulators treat biometrics in practice. In 2019, the Swedish data protection authority fined a municipality 200,000 SEK for using facial recognition to track student attendance in a school pilot. The lesson wasn't “never use the tech.” The lesson was that convenience isn't automatically a lawful basis for biometric processing, especially when consent isn't truly optional.

Governments and law enforcement keep pushing for these systems because time matters in investigations and security screening. Identification at scale can shorten manual work and widen the search space. That is the argument. The counter-argument is also straightforward: the same capability can become authoritarian when it is deployed broadly, with weak transparency, weak opt-out paths, and unclear retention rules.

When you combine remote cameras, searchable databases, and low marginal cost per query, the system doesn't need to be perfect to be powerful. It only needs to be cheap and hard to contest.

As was said by head of policy at the European Digital Rights, Diego Naranjo:

“With one single image, authorities can find out everything about you. That seems terrifying. It’s the normalization of mass surveillance.”

But what if the system goes wrong?

There are still serious risks of being misidentified. In high-stakes settings, innocent people can be flagged as “wanted suspects” because of false positives. That isn't a minor inconvenience. It can trigger police stops, detentions, loss of access, or downstream database contamination.

Two failure modes matter in practice:

False positives (wrong match): the system links you to someone else.

False negatives (missed match): the system repeatedly fails to recognize the right person, which often gets framed as “user error” until patterns show up across groups.

“These data-centric technologies are vulnerable to bias and abuse,” Joy Buolamwini warned while studying commercial facial analysis systems. Her broader point still holds: even if average accuracy improves, uneven error rates and misuse risks don't disappear on their own.

Buolamwini’s best-known result (with Timnit Gebru) came from the Gender Shades work, which tested commercial gender classification (not identity recognition). It found large accuracy gaps across skin tone and gender presentation, with error rates as high as ~35% for darker-skinned women in that setting.

That distinction matters because many real deployments mix tasks: a vendor may sell “face recognition,” but the product bundle often includes face detection, attribute inference, and identity matching. Bias can enter at multiple points, and the harm depends on the use case.

Independent testing is also less reassuring than vendor demos. NIST’s work on demographic effects in face recognition found that, for some algorithms and datasets, false positive rates differed substantially across demographic groups, sometimes by orders of magnitude, depending on the algorithm and scenario.

The conclusion isn't “facial recognition never works.” The conclusion is: if the consequence is serious, “works in general” isn't a safety argument. You need measured error rates in your environment, plus a policy that prevents a match from becoming an automatic decision.

The technology that is treated with caution in many regions has scaled aggressively across Asia, especially in China, where facial recognition shows up in everyday access control and consumer settings. Claims about a single, unified “social credit score” often oversimplify what is actually a patchwork of regulatory and compliance programs, but the surveillance footprint is real.

The “most surveilled cities” numbers get quoted a lot, and they should be treated as estimates, but they illustrate the direction of travel. Comparitech’s city-level estimates have included very high camera-per-capita figures for places like Shanghai (hundreds of cameras per 1,000 people in their methodology).

What changed recently is that even China is tightening rules around consumer-facing facial recognition in some contexts. Reuters reported that new regulations from China’s Cyberspace Administration emphasize that individuals shouldn't be forced to use facial recognition for identity verification, and that organizations must provide alternative options, obtain consent, and post visible signs where facial recognition is used. The same report notes these rules don't cover use by security authorities for surveillance or law enforcement.

The pattern is consistent across jurisdictions: governments like the efficiency. The public reaction depends on whether consent is real, whether alternatives exist, and what happens when the system is wrong.

Final thoughts

Facial recognition will keep expanding because it saves time and reduces friction. That is exactly why it needs constraints. Without constraints, “convenience” becomes the default justification for surveillance.

The future is not decided by whether the technology exists. It is decided by whether systems are designed so that consent is real, retention is minimal, errors are measured, and expansion is not the path of least resistance.

FAQ

What is facial recognition?

Facial recognition is a biometric technique that converts a face image into a numerical representation (an embedding) and compares it to other embeddings to verify or identify a person. In practice, “facial recognition” is often bundled with face detection and face analysis, which increases the risk of misuse.

What is the difference between face verification (1:1) and face identification (1:N)?

Verification asks “are you the same person as the reference on file?” Identification asks “who are you among many possible identities?” Identification is typically higher risk because it can be run at scale, including in public spaces and without the person initiating the interaction.

Is a facial image “biometric data” under GDPR?

Under GDPR, biometric data means personal data from specific technical processing of physical or behavioral characteristics that allow or confirm unique identification, explicitly including facial images as an example.

In plain terms: a normal photo isn't automatically “special category,” but once you process faces for unique identification, you enter biometric territory.

What does the EU AI Act restrict for facial recognition in public spaces?

The AI Act includes prohibitions and strict limits around real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement, with narrow exceptions and conditions such as prior authorization and safeguards.

It doesn't “ban all facial recognition,” but it narrows the most surveillance-like forms.

Why do false positives matter so much in facial recognition?

A false positive links an innocent person to someone else. In policing or security workflows, that can trigger stops, questioning, detention, or a chain of automated suspicion that is hard to unwind. At population scale, even a low false match rate can produce many wrong hits.

What do FAR and FRR mean in face recognition?

FAR (false accept rate) is how often the system matches the wrong person. FRR (false reject rate) is how often it fails to match the right person. Tuning thresholds is always a trade-off, and the “right” setting depends on the consequence of being wrong.

Is facial recognition biased, or just “not perfect”?

Both can be true. NIST has documented demographic differentials in face recognition performance, including differences in false positive rates across demographic groups depending on algorithm and scenario.

“Accuracy” without subgroup breakdown is not a safety claim in high-stakes use cases.

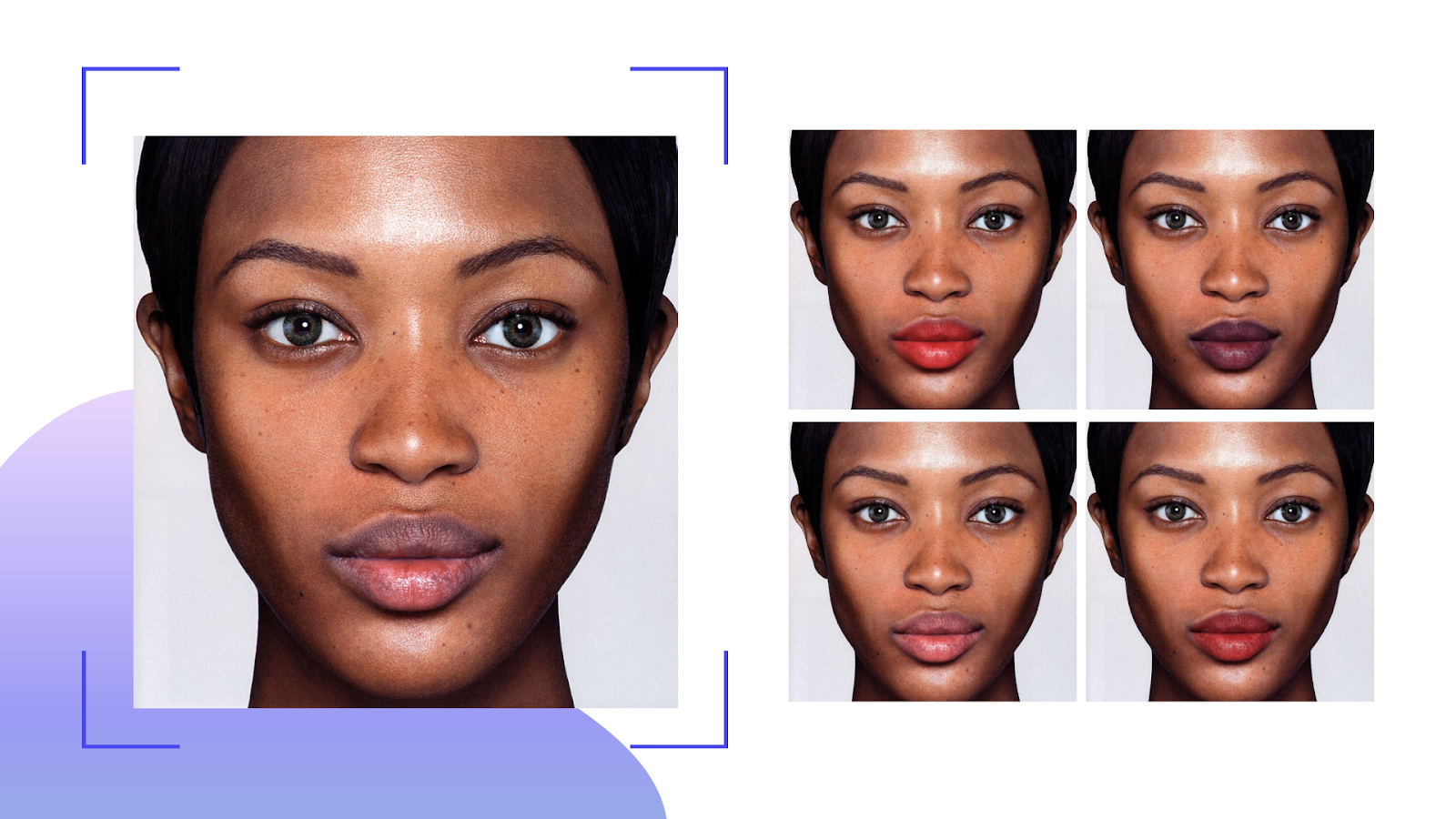

Does image enhancement make facial recognition easier?

Sometimes, yes. Improving resolution, reducing compression artifacts, or restoring facial detail can increase the amount of usable signal in a face image, depending on the model and pipeline. That's why face enhancement should be treated as a privacy-adjacent capability in any product that processes portraits at scale, with clear consent, retention limits, and opt-out paths where applicable.